The story of how The Cross Sea came together reads like something a novelist would invent: Toronto songwriter Anna Mērnieks-Duffield (of Beams and Ace of Wands) blows a fuse in her amp while on tour, the repairperson turns out to be Kevin S. McMahon — producer of records for Swans, Real Estate, Pile, Titus Andronicus, and The Walkmen — and a creative friendship ignites. Years later, Mērnieks-Duffield discovers she’s pregnant, feels the particular urgency that only an approaching life change can generate, and sends McMahon a batch of songs too raw and restless for either of her existing bands. He doesn’t re-record them. He builds onto them. Their mutual friend Daniel Liss — a filmmaker and musician finding his way back into sound — joins the sessions, and what emerges across two “Rock Camp” weekends at McMahon’s Marcata Recording, a 200-year-old barn studio in New York’s Hudson Valley, is a record that feels genuinely unpredictable from moment to moment.

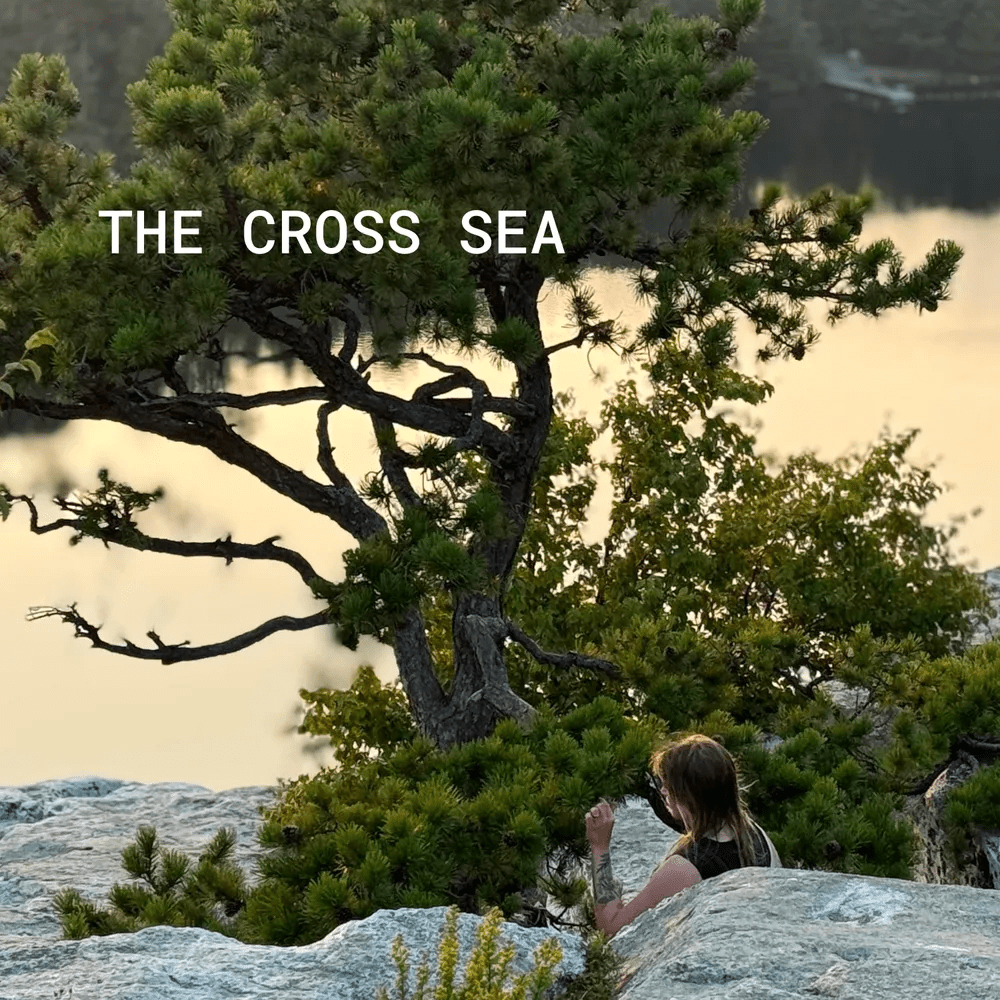

That unpredictability isn’t a bug. The band’s very name comes from a nautical phenomenon — when two wave systems moving in different directions intersect, producing a surface that looks almost quilted while the water below churns dangerously. As a self-description, it’s precise. The Cross Sea’s self-titled debut, out February 13 via Be My Sibling, holds acoustic calm and fuzzed-out chaos in the same hand without letting either fully win.

The album opens with “The Me That Waits for Me at Marcata,” which begins in a lull — clean acoustic guitar, Mērnieks-Duffield’s voice close and measured — before the full band tears through like a door coming off its hinges. The contrast isn’t jarring so much as clarifying: this is what the album is going to ask of you. The lyrics double as the record’s thesis statement. “The closer I get, the chemicals flood my brain,” she sings, and the song tracks the gravitational pull of a creative space, a place, a feeling that reshapes you just by proximity. Her pupils dilate “hard to let her in.” Somehow she knows “the end’s where it begins.” McMahon’s production honors the home-recording rawness of the original demo while expanding its architecture outward.

“Just Like Adrianne” operates in a different register entirely — witchy, surreal, and dense with imagery. Bats and birds burst from “technicolor explosions in flower form.” Shadows get mistaken for night birds. Time predates itself: “in the dark before dark became a rule.” The song moves between French and English, between clarity and dissolution, and the refrain — “I know you, I swear I do” — arrives like a recognition that can’t fully be explained or trusted. It’s one of the album’s most lyrically ambitious moments, the kind of song that rewards re-reading the words alongside the listening.

“There’s No Way” strips things back to their bones: breath, descent, a cave, and the knowledge that comes from going all the way down to something’s end. The resolution — “there’s no way I’m going now” — isn’t defiance exactly. It’s more like the calm that arrives after you’ve stopped fighting the understanding. “Eye of the Doe” occupies similar art-rock territory, anchored by one of the record’s most striking images: the white stag with the eye of a doe, running “tirelessly / the echoing sides of / the endless boreal road.” The song opens with a confrontation — spit flying, eyes white with rage, every flaw laid out — and then pivots into a chase that has nothing to do with the person doing the accusing. The muse doesn’t care about your arguments.

“Alien (Hold On to What You Love)” is the album’s most explicitly political track, and Mērnieks-Duffield doesn’t soften it. The song’s central image — a “psychotic, pill popping / money changer” who sets his own family home ablaze — hits with the blunt force of a parable. The repeated insistence that “money don’t love you back” functions as both a warning and a lament, and the song’s emotional core is the counter-argument: find something to love, hold it, fight for it. Against total despair, love isn’t sentiment. It’s a strategy.

The gentler songs — “So It Goes,” “We Won’t Be Alone,” “The Midwest” — each carry their own weight without straining for it. “So It Goes” balances the admission of fear against the refusal to be tested, ending on the quietly devastating confession: “I might reveal that I was lying.” “The Midwest” watches someone disappear into illness with the helpless clarity of someone who loves them and can do nothing. The prairie sunset at the end isn’t a resolution. It’s where the music stopped, and the thinking began.

Touchstones like PJ Harvey, Kate Bush, and Big Thief hover in the background — not as blueprints but as a shared vocabulary, a way of understanding what this kind of record is trying to do. What The Cross Sea adds to that lineage is particular to these three people: Mērnieks-Duffield’s searching, hook-complicated songwriting; McMahon’s production instinct for murk cut with crystalline moments; Liss’s presence keeping the dangerous edges just dazzling enough. When wave systems collide, the results are unpredictable. This one is worth the risk.

Leave a Reply