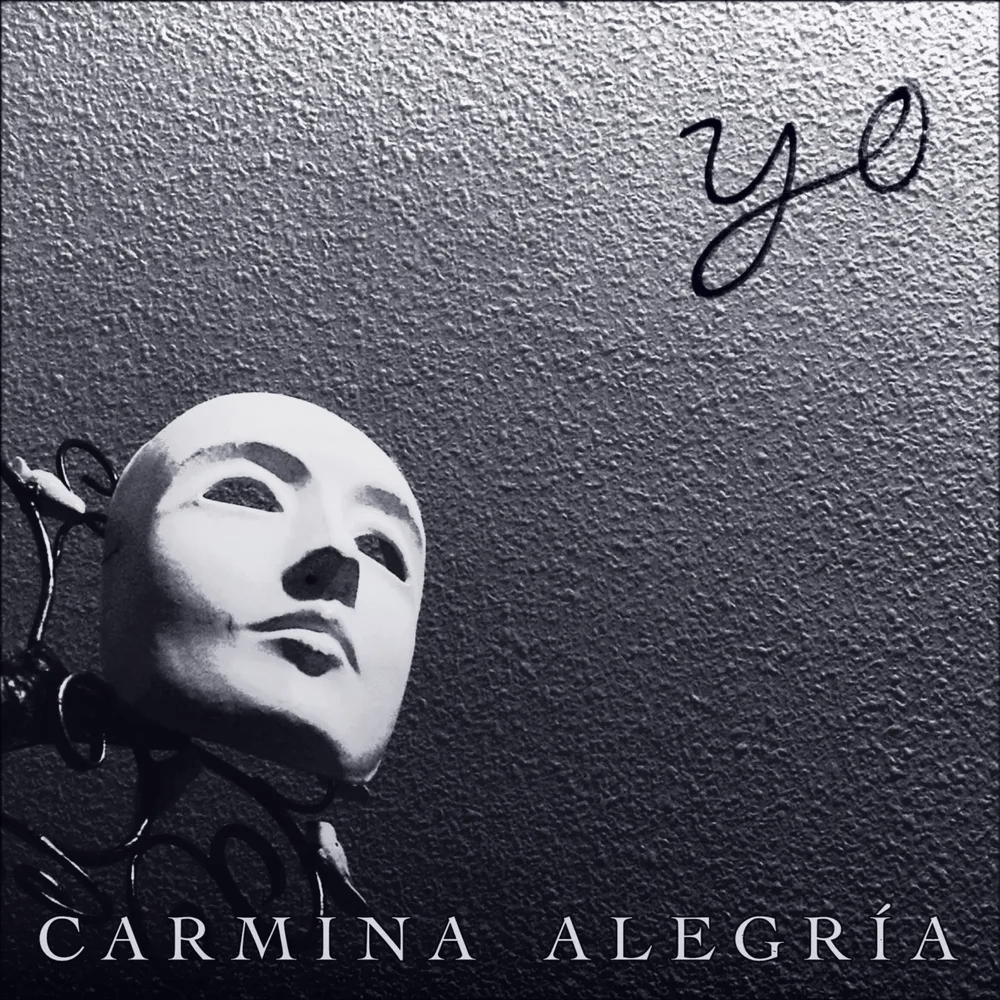

David G. Borrero constructs monuments for the forgotten. His grandmother Carmina Alegría nearly became a radio star decades ago—producers picked her stage name, saw potential, then life intervened and the opportunity vanished. She never made her record. Borrero, working under the moniker Yo, spent years unknowingly creating one for her, assembling pieces that only revealed their purpose the night she died. What emerged is thirty-four minutes of neoclassical ambience and post-rock architecture that functions simultaneously as tribute, narrative, and grief document.

The album operates through repetition and absence. “Carmina Alegría” introduces themes that later tracks will revisit, her recorded voice woven into warm arpeggios and dreamy production. The atmosphere reads as remembrance rather than mourning—this is celebration of presence, documentation of what existed. Then “Los muertos siempre son verdad” returns to identical musical material with one crucial subtraction: her voice disappears. The same home with nobody inside. Borrero understands that sometimes the most devastating statement comes from showing what’s missing rather than describing loss. Music proves particularly suited to this approach—you can play the exact same notes twice and create entirely different emotional experiences based solely on what you remove.

This structural choice elevates Carmina Alegría beyond standard ambient releases. Many artists in this territory prioritize atmosphere over architecture, letting tracks float disconnected from each other in service of mood. Borrero builds deliberate narrative arc, each piece functioning as chapter in larger story. “Desaparecer” opens as overture, introducing motifs that subsequent tracks will develop. The arrangement crescendos then settles, establishing both the album’s sonic vocabulary and its dramatic pacing. Nothing here exists accidentally—every choice serves the complete work.

The production maintains consistent spatial quality throughout. Synthesizers breathe rather than pulse, shaped with minimalist sensitivity into long pads and translucent harmonics. The electronic elements blur deliberately with organic sounds—bowed guitars, strings, room reverbs—until distinguishing digital from acoustic becomes irrelevant. This porousness reinforces the album’s central preoccupation: boundaries between presence and absence, memory and reality, the living and dead prove more permeable than we typically acknowledge.

Rhythm operates as suggestion rather than drive. Barely perceptible pulses surface through bowed strings and gentle percussion, creating temporal disorientation that mirrors how grief disrupts normal time sense. Forward momentum matters less than interior unfolding. Borrell suspends listeners in psychological space where minutes stretch and compress unpredictably, where the recent past feels simultaneously immediate and impossibly distant. The subdued rhythmic approach allows emotional nuance to emerge without competition from propulsive elements demanding attention.

“Coágulo de un instante” translates roughly as “clot of an instant”—time frozen, moment suspended. The track flies close to water’s surface, hovering between states. Then “Volver al aire” ascends dramatically, operatic vocals weaving through dense harmonic structures. Borrero described the title as meaning return to air, life as parenthesis between non-existence before birth and after death. The theatrical quality intensifies here, the album fully embracing its nature as performance rather than mere documentation. The vocals don’t narrate or explain; they exist as texture and emotional signifier, another instrument in service of the larger composition.

“Siempre (la mano en el fuego)” grounds the album back to earth with thunderous percussion and flute whimsy, guitars providing energy that earlier tracks withheld. The track represents survival—human spirit persisting through loss, finding ways to continue despite absence. The neoclassical theater influences Borrero draws from become most explicit here, the drama unsubtle but earned given what preceded it. After sustained introspection and floating atmospherics, the album needs this moment of embodied energy.

“Decirlo a veces sin palabras”—”to say it sometimes without words”—closes the main album by revisiting elements from each previous track. Bowed strings and airy textures cycle through the narrative’s key moments, the entire arc compressed into final statement. The piece concludes with a cappella family recording, voices chanting “Carmina Alegría” together. The gesture borders on sentimental but lands because Borrero earned it through restraint everywhere else. After maintaining considerable emotional control across seven tracks, allowing this moment of direct feeling reads as release rather than manipulation.

The bonus track “Levantando las manos” functions as encore, brief but intense spotlight moment. Its brevity works—after the album proper achieved closure, extending further would dilute impact. Instead, this final dramatic gesture acknowledges the theatrical framing the entire project embraces.

Borrero’s background in award-winning poetry becomes evident in the narrative sophistication. The decision to repeat the title track without his grandmother’s voice demonstrates understanding that emotional impact often comes from structure and omission rather than addition or explanation. Many musicians understand sequencing; fewer grasp actual narrative architecture. The difference matters. Sequencing arranges songs in pleasing order. Narrative architecture builds meaning through how pieces relate across time, how earlier moments inform later ones, how repetition with variation creates significance beyond individual tracks.

The “Yo” moniker—Spanish for “I”—provides deliberate anonymity. Borrero explained in interviews that hiding behind a generic pronoun shifts focus from artist personality to the work itself. The choice reflects discomfort with emotional exhibitionism common in contemporary music. By calling himself “I,” he paradoxically disappears, becoming anyone, the specific grief universalized. The album belongs to Carmina Alegría, not David G. Borrero. He simply built the monument.

Whether Carmina Alegría works outside its conceptual framework remains open question. The tracks function cohesively as complete album but whether individual pieces sustain interest divorced from narrative context seems less certain. The ambient and neoclassical elements, while executed with considerable craft, don’t necessarily break new ground within their genres. What distinguishes this record is the narrative ambition, the way Borrero uses familiar sonic tools to construct actual story rather than mere atmosphere.

At thirty-four minutes, the album maintains ideal length for its approach. Much longer and the sustained melancholy might become exhausting; shorter and the emotional arc wouldn’t complete properly. Borrero demonstrates understanding that concept albums require precise pacing—too much space and listeners lose thread, too compressed and nothing breathes.

Carmina Alegría ultimately succeeds as what it intends to be: the record his grandmother never made, given to her posthumously by someone who loved her. The album functions as closure and continuation simultaneously, completing her story while beginning his. She gets her stage name on an actual release. He transforms private grief into public art. Everyone who nearly became something but didn’t—nearly famous, nearly successful, nearly realized—receives acknowledgment through this proxy. The radio people saw potential in Carmina Alegría decades ago. Her grandson proved them right, just several decades late and through entirely different medium. The tribute stands, luminous and obsessive, proof that some debts get paid even after death.

Leave a Reply