The musical distance between East Coast farmlands and Southern California beaches seems vast until you hear Mark “The Ram” O’Donnell navigate that terrain with startling ease. On “I Am Nowhere, I Am Everywhere,” his follow-up to 2023’s “Songs of Wanderlust,” O’Donnell creates a sonic triptych that spans the American landscape while maintaining the intimacy of a personal journal. Across nine tracks and 45 minutes, he unifies disparate geographies through memory, storytelling, and a deeply rooted sense of place that transcends mere location.

Recorded with his live band in Carlsbad, California, the album transforms what began as singer-songwriter demos into fully realized arrangements that enhance rather than obscure the material’s fundamental honesty. The production throughout maintains a warm, lived-in quality—polished enough to highlight musical intricacies while preserving the spontaneity of live performance. This approach serves O’Donnell’s songwriting particularly well, as his narratives benefit from presentation that prioritizes emotional authenticity over technical perfection.

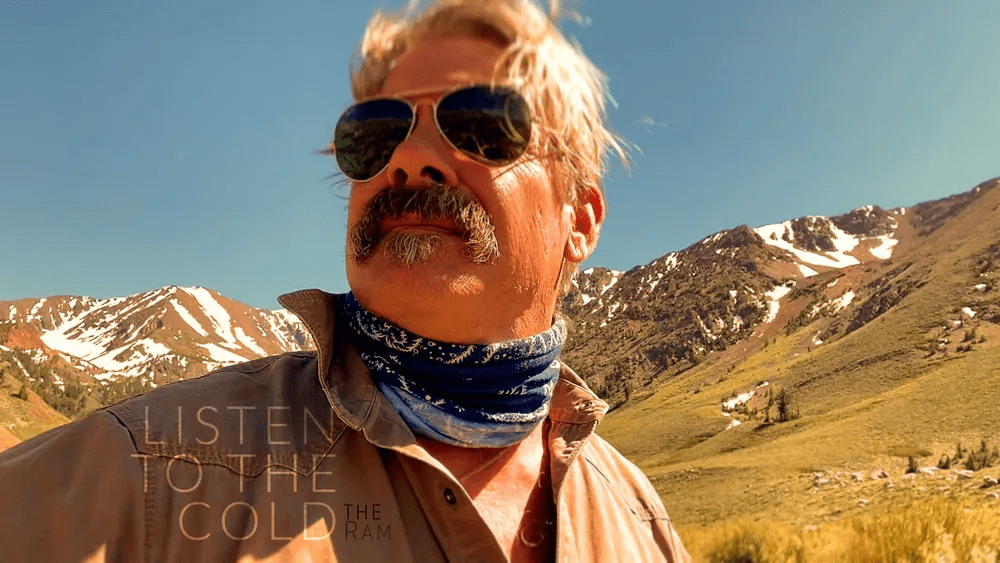

Opening track “Listen to the Cold” establishes the album’s preoccupation with absence and memory. Written during winter on his family’s Pennsylvania farm, the song grapples with generational loss while finding solace in natural continuity. O’Donnell’s vocal delivery here sets the tone for the album—conversational yet precise, with a weathered quality that lends authority to his ruminations on time’s passage. The arrangement builds patiently, allowing space for both lyrical detail and instrumental conversation.

“The Moon’s Loving Light” shifts perspective toward formative community, exploring how creative connections shape identity. Drawing from O’Donnell’s experiences at SUNY New Paltz in the late 1980s, the track creates a nocturnal atmosphere where celestial imagery mirrors artistic awakening. What distinguishes the song from standard nostalgic fare is its recognition that creative communities function as chosen families—particularly significant for those distanced from biological roots.

By the time “Love Is a Terrible Thing to Waste” arrives, O’Donnell has established his gift for transforming potentially harrowing urban experiences into affirmations of resilience. His matter-of-fact recounting of youthful adventures in East Coast cities—Philadelphia, New York, Camden—avoids both romanticism and cautionary finger-wagging. Instead, the song acknowledges how close encounters with danger can clarify what matters, with O’Donnell’s band providing a rhythmic urgency that reinforces the narrative’s forward momentum.

“Unbound” emerges as the album’s philosophical centerpiece and title source. Written during the pandemic, the track functions as both personal manifesto and universal statement on creative liberation. The band’s performance here achieves a rare balance between rhythmic discipline and expressive freedom, complementing lyrics that explore the paradoxical nature of being simultaneously nowhere and everywhere—a state familiar to both touring musicians and those navigating life’s transitions.

Instrumental interlude “Flip Jam” provides necessary breathing room while showcasing the intuitive communication among O’Donnell’s bandmates. Rather than mere showmanship, the track establishes further context for the album’s exploration of how community shapes individual expression.

“Everything,” written after a morning surf session, demonstrates O’Donnell’s ability to find philosophical depth in everyday experience. The song’s contemplation of beauty amid apparent emptiness feels particularly resonant coming from someone equally at home in urban galleries and rural landscapes. The arrangement builds with methodical patience, paralleling the gradual recognition of abundance in seemingly barren circumstances.

“Perpetual Change” addresses mortality with unusual directness, examining how ancestral connections provide both grounding and forward momentum. O’Donnell’s unflinching acknowledgment of his own aging—white hair and weathered face contrasting with youthful internal experience—creates a poignant framework for broader reflections on life’s brevity and the imperative to focus on what matters.

“Join Along” offers the album’s most playful narrative, recounting a youthful Grateful Dead concert adventure that left O’Donnell and friends stranded in late-night Manhattan. The track’s blend of humor and reverence captures how seemingly random experiences often reveal their significance only in retrospect. The band’s performance here achieves the loose-but-tight quality that characterized the Dead’s best work, creating musical concordance with the lyrical content.

Album closer “Warmth of the Fire,” also written on the family farm, completes the geographical and emotional circle begun with the opener. This meditation on rural community and familial legacy avoids sentimentality through specific detail and clear-eyed observation. When O’Donnell sings about neighbors watering their horses near the family farmhouse, he transforms personal memory into universal recognition of how interdependence sustains both individuals and communities.

Throughout “I Am Nowhere, I Am Everywhere,” The Ram demonstrates remarkable skill at unifying apparent contradictions—East and West, urban and rural, personal and universal, presence and absence. Like the best singer-songwriters, O’Donnell understands that specificity creates universality rather than limiting it. By grounding his philosophical explorations in concrete experience, he creates an album that functions simultaneously as personal document and communal invitation—a musical manifestation of the family ethos that clearly shaped him: seeing the best in your surroundings while being your best for those who depend on you.

Leave a Reply